January 2026

My 6 or 7 Reflections on Stranger Things and the Return to School

(An odd title for this month’s blog - but I hope it all makes sense in the end.)

The TV phenomenon that was the final series of ‘Stranger Things’ may or may not have grabbed your children's attention (and yours as well) over the break; I will admit that it did grab mine, as I have seen every episode from season 1.

If it is something that has passed your family by, then this is definitely not a recommendation to watch it; indeed, I certainly would not recommend it at all for our younger Secondary students, as there are some seriously scary and intense moments - so please do not think I am asking you to advise your children to watch it! But for some of our older students, with the show’s first airing being 9 years ago with a set of actors being 11-13 years old, they will feel like they have grown up with these characters - that gives a tremendous amount of belonging - and like me, they would have been eagerly awaiting the final showdown of the show to see if the characters would be victorious over evil.

While the theme of the show will not be for every family’s taste - it is based on an evil being from another dimension threatening a small town in the US - at its core is a story of how a group of eclectic school friends have to work together, find strength and courage from each other and the bond they have, to achieve amazing things - all because they have the strength of working as a team.

The creators have been clever too - as although it may be aimed at teenagers in many ways, it is also aimed at people of my generation too: it is set in the 1980s, when I grew up, and has a number of 1980s classic film references - Dustin saying “Here goes nothing” as he enters the final battle mimicked Han Solo’s phrase as he starts his Death Star run with the Millennium Falcon in Star War’s ‘Return of the Jedi’. And the soundtrack brought back a whole host of musical memories - Kate Bush and Tiffany being two (almost) classics from my youth.

There was a central theme in the show - the characters played the role playing game ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ - another one of my confessions is that in the 1980s, I spent (probably) hundreds of hours with my pals playing D&D - I would definitely have been in the Hellcats. It is a game that works by a set of complicated rules, which transports players to a land where imagination brings adventures to life - decades before CGI could do it for you. These campaigns were about more than who won - there was strategy, knowledge acquisition, and imagination - much more than when playing today’s computer games, where all that is done for you.

The main thing about the show is that it got me to reflect on societal needs - especially for school aged children. Humans are animals that thrive off of togetherness, shared experiences, and friendships. We seek (particularly in those formative teenage years) others who share our understanding, our views, our likes; people about whom we can say: ‘they are like me’, or ‘they support me’, or ‘they are my friend’. Ultimately, Stranger Things, beyond the magical monsters and alternative dimensions, was about friendship, loyalty, and togetherness. And maybe it reminded us old folk about the joy of just being with a group of friends, laughing at the same ‘in’ joke (more of that later), and spending time together; before the drudgery of adulthood - days of work, stress, and the seriousness of being a provider and carer for others.

This is why the first day back at school is always bittersweet…The end of the holiday (and what a lovely long holiday it was) is always a sad day; but it also brings sweetness for most students, in the return to the place where students gather with their friends to share similar reflections, and to be socially driven again. Shared goals, dreams, collectiveness, togetherness, BSAK culture. Collective identity that a school like BSAK brings. A psychological safety net, where there is togetherness in a place where those in charge allow creativity, encourage friendly relationships, and (as warm demanders), still expect the best while supporting with care.

I’m not sure there are 6 or 7 reflections here - but it was a great way of threading in the other phenomenon that hit just before the break - the ‘in’ joke of ‘6 7’, or ‘6 or 7’ (cue a smile, or even hilarity if you are in on this joke). This is a classic example of societal shared consciousness creating togetherness through laughter. The joke is pure absurdity, of course; but to get the joke and to giggle at spotting one (when someone mentions the numbers 6 and 7 in that order in the same sentence) is the social togetherness that humans crave so much. The surge of dopamine that the children receive when they spot one (hugely increased if they are with others who spot it too but they are the first ones to recognise it), and increasing exponentially if an adult around them gets annoyed or confused as they are not ‘in’ on the joke - is huge!

So don’t get annoyed by ‘6 or 7’ (“giggle”) - embrace it. Just like “Whassup” (if you remember that), or the Crazy Frog from the 1990s (which I found most annoying rather than funny), the ‘6 7’ time will end, and the children who now find it hilarious will look back and not understand why it was funny, and probably not understand the need they had to find it funny - but that need is a similar need to why each generation craves a show like Stranger Things, or a game like D&D: social togetherness. Humans want to bond. They want to band together and share experiences that say ‘I’m with you’. As schools, and as parents, we should embrace that, and allow as many opportunities for that for our young people as possible. It is why we have such a drive on CCEs and the House system at BSAK. Because life as a Secondary Student goes beyond just learning. Learning is vital - of course it is - one of our key jobs is to ensure that all of our students exceed their own expectations and continue their journey beyond BSAK with the best institution they can, with the best academic results possible. However, we also want them to feel the culture of belonging at BSAK; the culture of walking through our corridors and going into classrooms with people who are very different in many ways to them; but are also people who are familiar, together, who share experiences with them, are loyal to them: who are their BSAK family.

With my warm regards,

Nigel Davis

December 2025

Celebration Tea

I am taking the opportunity with this blog to let you all know about a recent initiative I have started - which I feel is going rather well, and hope will be cemented into a tradition. There are few things more synonymous with the British than a cup of English Breakfast tea. At the British School Al Khubairat, I am combining that with a celebration of our students.

Each Friday for the last month, I have started to meet individuals or small groups of students whose success is worthy of celebration, and we have a cup of tea to start our final day of the week. So far, I have met with students who: have had their poetry published into their own book; have been recognised for achieving the best GCSE results in the World, or in the UAE; students who are preparing for interviews at Cambridge university; and students whose prowess in the school show for acting and singing was simply exceptional.

I have a 25 minute slot with them. This is a time to pause, celebrate, tell them how proud we are of them, and discuss their inspiration, what drives them, and their hopes and dreams for the future. They will one day leave BSAK, and I am excited to see what gifts they are able to give to the wider world. All this while enjoying the world’s most popular drink (after water) !

This is one of the great privileges of leading the Secondary School: witnessing the many ways in which our young people shine. Every day, students demonstrate remarkable dedication - whether that is in the classroom, on the sports field, on stage, or through the quiet kindnesses that make our community stronger. Selecting students each week who have demonstrated exceptional achievement, and bringing them in to show how much they are appreciated, has been both humbling and inspiring.

Looking forward, I intend to continue with these Friday Morning Tea times. I am looking forward to meeting with many many students. I will be looking for students who have had a standout moment in sport, an impressive academic milestone, a memorable performance in the arts, an act of kindness, or an example of genuine school spirit. The purpose is simple: to pause, to notice, and to celebrate.

But why do I think that this is so important?

There are many reasons for singling out and celebrating success. Many students do have confidence, but (especially) as they grow through their adolescent years, many do not - even those with tremendous success. Taking time to recognise achievements helps students to internalise the message that they are capable, and helps cements self-belief.

When we highlight a student’s resilience, creativity, leadership, or kindness, we send a powerful signal about the values we cherish. It encourages BSAK’s young people to repeat the behaviours that enrich our learning environment and helps shape them into thoughtful, capable adults.

Highlighting exceptional students' achievements to the rest of the school helps to create an even stronger culture of aspiration at BSAK. Public celebration does more than acknowledge one success, the hope is that it inspires many others. When students see their peers recognised, it raises the bar for everyone and helps build a community where excellence is expected, and admired.

It is also about nurturing character. Importantly, not all achievements are about winning. I hope that many of the students I will be meeting may be celebrated for the journey as much as the outcome - through their persevering through difficulty, supporting others, or demonstrating integrity. These moments reflect the character we hope to instill in all our young people.

This new weekly celebration is more than a meeting; it is another way of reinforcing our core values that sit at the heart of BSAK’s community. I will not be putting all of their stories in the monthly blog, but from time to time, I will look forward to sharing these uplifting stories, and I know you will be just as inspired by our students as I am.

With my warm regards,

Nigel Davis

November 2025

The Disengaged Teen

In the last week of June this year, Mr. Leppard gave all of the Secondary SLT a present - the book above: The Disengaged Teen, written by Jenny Anderson and Rebecca Winthrop. It was a present that combined two of the senior team’s passions - helping young people be the best they can be, and reading for self-improvement.

It has been a really interesting read, and I would like to share my takeaways from it, as I really feel that parents can take away a huge amount from the book - and I wish I had read it when my daughter was 12 (sadly, she is now 24, so well passed the teenage years!). The book is US centric; however, the learning from it is transferable, I am totally sure. For many parents, who may be smugly turning off of this blog as they are feeling safe that their children are all OK, that is great… But equally, I know that if you are starting to read this as it is of interest for you in your current situation - you are NOT alone!

In some ways, the book is a little depressing - or at least starts off that way. There is a particular image from the book that will resonate with many parents of teenagers… It shows a speech bubble from a parent, asking “How was your day?” The teenager’s speech bubble response was “Fine”. However, the thought bubble coming out of the teenager shows what they really think: ‘I didn’t understand anything in Biology and 'my Art teacher is unfair', and 'one kid was a jerk in class…’ so “Fine” is just the easiest answer so that they will be left alone. This response can quickly lead the parents of teenagers to stop asking (I know I did) when you get that type of response - life is too short, and you want a lovely relationship with your children, so when you get too many negative responses to questions about schooling, it often does seem easier to just stop doing it.

Many of us can remember the ‘change’ from pre teen to full blown teenager (and if you are from the UK and of a certain age, you may remember the Harry Enfield comedy sketch of when the character Kevin changes into a teenager monster as soon as the clock turns midnight on his 13th birthday!). We notice the subtle but significant changes also as they move into the teenage years: the engine doesn’t quite rev as it used to. The spark of curiosity, and the unquestioning willingness to work as hard as they can… may begin to falter. For many families at BSAK, this is a moment of mounting questions: Is my child turning inwards? Are they turning lazy, or is something deeper at work? Anderson and Winthrop argue that what we often label as “laziness” or “attitude” in teenagers is more often a complex, layered phenomenon of disengagement - not only from school tasks, but from learning, from meaning, and sometimes from hope. If you are noticing this, or start to - you are not alone - and there are things you can do about it!

Anderson and Winthrop studied thousands of children and families for the book. Although their research unveiled many struggling children and families, they also found amazing success stories, where children who had previously been hopelessly disengaged, rebellious, depressed, or directionless, can become engaged and can start to thrive. And parents who are able to engage their children into a love of learning, and model a love of learning, see the best results. And that questioning about school? Their research shows that students whose parents ask about their education score 16% higher on their Maths scores.

Many of our students are high achieving: the GCSEs, the A Levels, the extracurricular activities. In these settings, it’s tempting to assume students are fully engaged - but Anderson and Winthrop’s research warns otherwise.They identify four “modes of engagement”: Passenger, Achiever, Resister, and Explorer - which one is most like your child?

- A Passenger drifts: showing up, doing minimal work, perhaps still getting decent grades - but no internal spark - (BSAK has very few of these).

- An Achiever appears fully engaged: excellent grades, lots of activities - but is often driven by fear of failure, external metrics, and fragile self-worth. This is a category that BSAK does have representation in.

- A Resister pulls back completely - skipping work, acting out, or withdrawing. Thankfully, BSAK has almost none of these - these are incredibly challenging for both home and school, and requires careful support and teamwork from both.

- An Explorer is the peak mode: internally motivated, curious, self-aware and resilient. This is what we are all aiming for with our children. We may not get there completely, but Anderson and Winthrop give us some pointers for how we can work with our children to get them close to this category: As parents, if we shift the conversation: From “What grade did you get?” to “What did you learn, what surprised you, what did you struggle with?”; if you can encourage reflection: Asking your teenager to articulate their learning journey rather than simply the outcome; and if we can value process over result: Praise the attempt, the revision cycle, the self-check, the effort, rather than only the trophy.

As our children grow, their autonomy also grows, and our influence as parents arguably shifts. The book emphasises that parents often feel less able to help when adolescents pull away, and this can be really frustrating; yet - and this is good news - your role is more important than ever.

In a high-performing school like BSAK, where expectations (from parents, students, staff) are already elevated, parents may feel trapped between wanting to guide and needing to let go or being pushed aside.The push-pull of independence becomes sharp. Disengagement can sometimes be a signal: a cry for more meaningful connection, control, or respect.

What parents can do:

- When it comes to homework or studying, ask “How are you finding this? What’s confusing? What do you want to try differently? What is blocking you right now? Why not try a draft first if you are struggling”

- Collaborate rather than monitor: Work as a team with your child and their teachers - ask what support looks like, what feedback is emerging. And model calmness and curiosity (which I know is often much harder than it seems!).

- Focus on learner identity: Help your child see themselves as someone who learns, experiments, reflects - rather than just someone who gets grades. Within BSAK’s values of ‘endeavour & resilience’, we can lean into that learner identity. And that the journey is more important than the prize - that will take care of itself.

- Use our BSAK’s culture and identity - The student library, the enrichment clubs, the ‘BSAK Superstars’ displays: all of these reflect identity, belonging and challenge. Talk to your teen about how they find their place, and how they are influenced.

- Model curiosity - about things such as: your own reading, your hobbies and how application and resilience helps, how you make time for quiet reflection or new exploration: when your child sees you learning, they are more likely to feel permission to do so.

Parenting adolescents is by definition a transition, and what is clear is that the earlier you realise the challenges and make adjustments to how you are with them, the more impact it will have.

‘The Disengaged Teen’ offers us a powerful lens - four modes of engagement, tools for conversation, and a reminder that our role is not to control every outcome, but to guide the process of becoming. For BSAK parents, this means leaning into our school’s deep values and high-performance ethos, but also reminding ourselves: what matters most is not the grade our child gets today, but the learner our child becomes tomorrow.

With best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

October 2025

The heart-beat of a great school - the Modern School Library

This month, I am returning to something that is somewhat of a favorite subject of mine. I have written a few times about the power of reading; the impact it has on young people as they mature intellectually, and how it can truly inspire and change peoples’ lives.

I believe that for a school to be truly great, it must have a truly great library; and by that, I mean a truly great 21st century library. Today I will argue that our BSAK Secondary library is truly that: Great.

I am going to start with some wonderful quotes that I found online about libraries:

"I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of a Library."

"Nothing is more pleasant than exploring a library."

"Libraries store the energy that fuels the imagination. They open up windows to the world and inspire us to explore and achieve, and contribute to improving our quality of life."

"The only thing that you absolutely have to know, is the location of the library."

Not unsurprisingly, these are almost all quotes from famous writers - apart from the last one - which is attributed to the greatest scientist of all: Albert Einstein. Also unsurprising is that they were all made before the invention of the internet. They were from a time where books held the only answers and the only entertainment. Quite simply, libraries had to be the source of knowledge and understanding as well as the source of imaginative adventure.

Today, of course, is very different. We have not only information at our fingertips, but also entertainment; and with the invention of social media and now AI, that entertainment is incredibly powerful and addictive.

However… we must consider that our interactions with the internet and social media are different for us as adults than it is for developing children and teenagers. As adults we access social media and AI with the backdrop of already having the skills to get the best out of them; being able to read well enough to use them. We must guard against our youngsters of today trying to run before they can walk - what I mean by that is that they must not lose the sequential stages of development in their own reading, and the ability to use their own imagination to its very best, before they encounter all of what the internet offers.

A library obviously continues to be both an incredible source of information, and a collection of stories that can inspire a person’s imagination. A book can elevate a person’s intellect and wisdom, as well as make a person laugh, cry, love and find meaning and a sense of belonging! And the better we can read, the better we can fulfill so many other roles in life - a larger vocabulary is the best judge of a person’s ability (according to E.D Hirsch, as I have written about in previous months)... and this is best achieved through books, not through social media!

However; in 2025, a library needs to be so much more than just a collection of books. While we really must encourage our children to love books, and have a love of reading, we have to accept that (unlike in the pre internet era) information and entertainment is far more gratuitously available at our fingertips. So today, they must be far more than that. I believe that the BSAK Secondary library is just that.

The BSAK Secondary library is amazing. And is so much more than just a school library. Aesthetically, it is beautiful - a two story circular library is so unusual; I smile every time I go into it - especially entering from the top level, where Sixth Form students are left to silently bury themselves away into their work, their laptop, or a book. Looking down upon the library, with its central staffing section where Ms. Renda and Mrs. Lorgat are always smiling and supporting our students. Over the last few years they have reconfigured the library, including an Arabic majlis area which is now the most popular area for students to relax with a good book.

Our library is a hub of our school - its central location is not by accident. Every morning before the bell for registration, and during registration, there is a steady stream of students, with nearly a 1000 books per month often taken out; it is a place where every nationality and cultural background of our students is catered for - it is the most inclusive part of our school - and that is so important. There are sections for sixth formers with books from the reading lists of top UK universities, that help them look forward to the first year of undergraduate study. There is a growing section of Arabic literature and poetry. There are journals and newspapers, and over 12000 fiction books - from Harry Potter to Shakespeare. All ages and reading levels are catered for - including anime magazines and a ‘reluctant reader’ section. It also houses the online library - many different periodicals and online journals that students, especially those in GCSE years and Sixth Form are able to use to help with their studies.

Lunchtimes are an incredibly busy time in the library. For some BSAK students, it is their lunchtime go-to place; a place of true belonging. A place of peace; a place where they can immerse themselves; a place where quiet games of chess, Ludo and connect 4 are played.

Lunchtimes are also where we have special small scale performances - ‘Tiny Desk’ concerts where students play acoustic music - often for the first time in front of a smaller gathering of appreciative listeners. Last week we had 6 poetry recitals, where students (including our 5 Poet Laureates for this year) performed a combination of their own poems as well as reciting classics.

We have themed weeks in the library, such as Medsoc week where literature on medicine is put in focus, or Neurodiversity Week; displays such as ‘the Ronaldo or Messi debate’, and competitions - like the ‘Guess The Novel By The Opening Line’ competition. And of course, World Book Day, which is led by our library, with our DEAR (Drop Everything And Read) moments across the school leading up to and on World Book Day.

It is also a place where many of our Duke of Edinburgh volunteers and Work Experience students are able to find out more about a place of work, offering a friendly place to cut their teeth on life beyond being a student. It also brings over Year 6 advanced readers every year in terms two and three, where they can be energised about the new collection of books awaiting them, and choose age appropriate books to loan out to read which are more challenging than the Primary Library can offer.

What our Secondary School library is not, is a stuffy, dusty collection of books! It is a dynamic, friendly, happy, peaceful (and sometimes excitable and even loud!) place. It has moved with the times, never forgetting one simple truth: the pleasure of a good book is universal and will never end. It is truly a Great place!

With my very best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

September 2025

The ‘British Curriculum’ School

This month, I am writing about the ‘British’ Curriculum. We are obviously very proud to be a British Curriculum school and we are currently recognised as the ‘Best British Curriculum School in the UAE’ (Top Schools Awards). This is obviously a wonderful accolade; but I have been considering lately that some parents may not fully understand what ‘British Curriculum’ means - I imagine that there will be many parents for whom school is a distant memory, and other parents who never actually completed their schooling in the British system, so I hope everyone finds something useful in this blog.

In essence, it means that the school delivers education in almost exactly the same way as schools in England would (as opposed to the whole of ‘Britain’, where there are some stark differences between the different regions), known as the National Curriculum of England. There are some local contextual differences, which I will get to later. This British Curriculum schooling offers peace of mind for parents, in terms of it being a clear system that has been built up over a tradition of schooling which started hundreds of years ago. It is a system which is globally recognised, with the outcomes offering the opportunity to attend the best universities from across the globe.

In England, schooling starts with pre-school years - nursery schools or ‘Foundation stage’ schooling - FS1 and 2 as they are known in the UAE, for children aged 3-5. They then start their schooling (when the child is 5) in Year 1, and with each passing year move up a Year until their final year of schooling, which is called Year 13. There is a difference between the British Curriculum and both the UAE local schools or schools delivering the US Curriculum, as they work in ‘Grades’ rather than Year Groups. The Grade system is always a year behind the Year system - for example, if a British Curriculum student is in Year 7 (the start of secondary education), then the equivalent student in the local or US system would also be starting the phase known as High School and be the same age (11 years old), but would be going into Grade 6.

Throughout all the students’ time in the Secondary School, the golden thread that runs through it is the pastoral element. In the Secondary School, students have Form Teachers who they are with every morning for registration time (they keep the same one through Key Stages 3 and 4 and have a new one for Key Stage 5). These guide them, mentor them, and care for their daily needs as they move through the British Curriculum school.

In the British system, Year Groups are grouped together into phases known as ‘Key Stages’. They go from the youngest, Key Stage 1, up to the oldest (Sixth Form) also known as Key Stage 5. There are always 2 or 3 years in one Key Stage. I will only write here about those in the Secondary School:

Key Stage 3:

Students start their Secondary Schooling at age 11 into Year 7 - the first year of Key Stage 3 (which encompasses Years 7-9). The Secondary School is a massive step for young learners; the most significant is the movement away from one ‘class teacher’, who will deliver the vast majority of a primary school student’s learning, to specialist teachers for every subject. So a student moves from Year 6 where they may have one main teacher and a different teacher for 4 or 5 other subjects (e.g. languages, Music, PE, etc), to a Year 7 student, who could have up to 15 different teachers per week, in 15 different classrooms!

In Key Stage 3, students are taught the National Curriculum. The National Curriculum subjects have their own curriculum, which BSAK follows, although with more freedom than schools in the UK have. This is what mostly creates our timetable of subjects in Years 7 - 9. The exceptions to this are with our local context: For BSAK students who are Muslim and carry Arabic passports, they are obliged to learn the Ministry of Education subjects - Arabic as a language, Islamic Education and Arabic Social Studies. As we are the British Embassy school, students without an Arabic passport have Arabic language learning as an option, not a mandated language, as part of the Modern Foreign Languages (MFL) suite (along with French and Spanish).

The final difference to schools in the UK is the subjects of PSHE (Personal, Social, Health and Economic education) and the subject of Citizenship. In the UAE, Morel Education is mandated for students, which covers many of the aspects from PSHE and Citizenship, so BSAK has created a subject based on all three of these areas, called MELS (Moral Education and Life Skills).

As students approach the end of Key Stage 3 (in Year 9), they choose their Options - this means they choose the subjects they take on at GCSE in Key Stage 4. This is the first time for most students where they are able to exercise choice in their education. It is the first time that students, who are normally only 14 years old, have to consider their futures - decisions made at this age can impact university and career paths in their future. At this point, they are moving from 16 subjects down to 8 or 9 - their GCSE pathways.

Key Stage 4:

Key Stage 4 lasts for two years: Years 10 and 11. It culminates in the taking of the GCSE exams. The GCSE stands for the General Certificate of Secondary Education. These were introduced in 1988 (the year I actually took my GCSEs - I was the test year!). As an international school, BSAK is able to choose either the ‘homeboard’ GCSEs or the International GCSEs. You can tell the difference as the international ones are called iGCSEs. They are slightly different in their specifications - with the biggest difference being that the iGCSEs are less UK-centric; they are less likely to focus the exemplars used and the knowledge needed on the UK - this, for many subjects, is helpful for BSAK students as they often are not as familiar with the UK.

GCSEs are a crucial step in a student’s journey through the British educational system. Some subjects are compulsory - English, Maths, and at least two Sciences, and after this, there are a number of option choices. They are for virtually all students to take as they spread across virtually all ability levels. They are recognised across the world as the gold standard assessment of student attainment at the age of 16. They are used by schools as a gatekeeper to the next step - post-16 pathways; but not all students manage to make it through this stage into the post-16 pathways. In the UK, approximately 30% of 16 year olds do not manage to collect GCSE results which allow them onto post-16 studies. In BSAK, although our GCSE results are significantly higher than the UK average, there are still a handful of students each year who do not make it through to the BSAK sixth form.

A ‘Good’ pass at GCSE is considered to be a grade 4 or above. However, in order to demonstrate the level of understanding, conceptual skills and knowledge for the A Level pathway, at least a grade 6 is required, and for some subjects, a grade 7 or above is required.

Schools calculate their ‘Value Added’ for their GCSE results. This is a calculation based on the students’ starting points and where they end up (i.e. how much ‘value’ the school has provided against average expectation of the cohort). We use the Cognitive Ability Test (CAT4) that all students sit when they enter BSAK, and again at years 10 and 12, to gather their starting point. When schools have a Value Added of over +0.3 it is seen significant, and over +0.5 is deemed to be very good. The BSAK Value Added this year was +1.25, which is insanely good; this means that each grade was, on average, a grade and a quarter higher than the expected grade in that subject based on the student starting point.

Key Stage 5

This Key Stage covers the Sixth Form - Years 12 and 13. Students at BSAK follow two pathways (and sometimes a combination of both): A Levels or vocational BTECs. Currently, BSAK has the widest range of any British Curriculum school in Abu Dhabi, and one of the widest ranges in the whole of the Middle East: there are 24 taught A Level courses and 6 vocational courses (5 BTECs and 1 RSL Diploma).

The A Levels are the gold standard global post-16 qualification. The ‘A’ in A Levels stands for ‘Advanced’ Level - indicating the level of achievement it takes to get onto these courses and succeed in them. Students typically take 3 A Levels, although if they choose Further Maths and Maths, then they will take 4. Rarely, we allow some students to choose 4; however, analysis of our BSAK results over recent years indicate that students who are allowed to follow this route do not perform as well as expected when compared to similar ability students who only chose 3 subjects. Mr Oakes (BSAK’s Head of 6th Form) has also visited many of the UK’s top universities, and the message from them is clear - they do not need, nor credit, students completing 4 A Levels - they only look for the 3 best A Levels; therefore, taking 4 is often a waste of effort for those students going to UK universities.

The BTECs and Diplomas are vocational (work based) learning courses. These curricula are more practically driven and are assessed by continual assessment with assignments, rather than with high stakes terminal exams. BSAK students thrive in these courses, as they are hard working, and dedicated; and these vocational courses are able to help them shine, and reach the university courses they dream of.

—-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This is a brief overview of what it is like in the ‘British’ Curriculum schools. We hold ourselves to the highest level of accountability within this system - pushing ourselves to provide the very best of British education; and the outcomes in terms of achievement in examinations do show that we do just that. The added dimension to BSAK is our Emirati roots, where we are able to merge with grand customs and cultures, to provide an incredible globally minded education for our students.

As ever, if you would like to ask any further questions or get in touch about this, please do contact me.

With Best Wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

June 2025

Sometimes something just clicks…

As exam season is now upon us, I am always tempted to write to parents about revision and exam preparation - and I will admit, that I got about three quarters of the way through writing this month’s blog about just that. However, I then realised that the last two years I have actually done this - so please read the blogs from April and May 2024, and March 2023 for posts about how students best prepare for exams.

But this month I have changed my choice - because I was directed by a colleague (as we were braving the increasing heat on a 50KM cycle ride) to a book I had not read - he told me he was sure I would like it, and he was not wrong! It is not a new book, but certainly resonated with me this month as I flicked my way through it. It’s a book about ambition without arrogance, success without selfishness, and excellence with empathy. It talked a lot to me regarding myself, current affairs, philosophy and psychology; and also how it could positively impact BSAK students - both now, and in their own futures. It also resonated with meetings I sometimes have with parents - whose own egos about their children are always well meaning - but sometimes can be creating issues for the child’s long term success.

Ryan Holiday’s book ‘Ego is the Enemy’ reminds us that our Ego really can be our enemy - and gives us clear and actionable ways of using it to our advantage, rather than letting it create negative outcomes for ourselves. Ego, as Holiday defines it, is the unhealthy belief in our own importance (or that of our children). It’s the voice in our heads that says “I’m special”, “I know better”, or “I shouldn’t have to do that”. It can inflate success and excuse failure. It blocks learning, because it assumes we already know.

In high-performing environments like BSAK, ego can be a hidden danger. Students praised for talent may become afraid of failure. Those used to success may avoid challenge. It’s natural – but limiting.The antidote? Remaining always a student who understands that they need to grow and not being afraid to fail - indeed, realising that failure is just another crucial step towards success. Michael Jordan (the world’s greatest ever basketball player) famously said “I have failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.” Our ego sometimes catastrophises failure - and parental egos for their children can often do the same thing. Parents and students should be wary of this - facing adversity or setbacks is a part of life that we all have to face; teaching our BSAK students how to overcome these challenges is so important - or else we risk teaching our students that any stumble should feel like a disaster.

This is a mindset we try to foster in school: growth over perfection, process over results. Students who seek feedback, ask questions, and learn from mistakes are laying the foundations for long-term achievement – even if they stumble from time to time.

Another key message is that ego is often most dangerous when things are going well. So never rest on your laurels - those who become the very best in any field don’t stop once they’ve achieved something; they use it as a platform to go further. These people see success not as a final word, but as a reason to work harder, stay grounded, and serve others. We want our students to carry the same perspective. A great set of test results is a step forward – not the destination, as is success on the sports field - lifting a trophy one year should spur you on to work even harder for the next challenge.

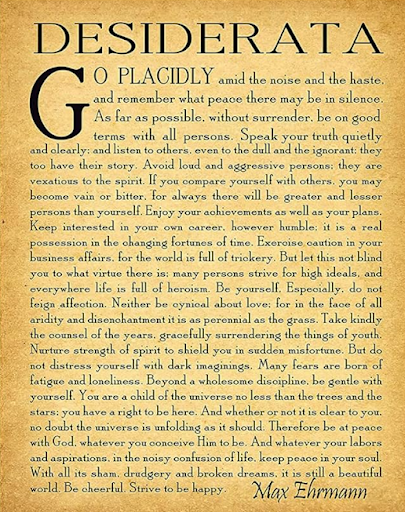

The final thing I drew out of the book was that having a core set of values with which to live our lives is truly vital. Holiday sets these out as being ‘Work hard, stay humble, be kind.’ If we think about it, if nothing else is learnt by our children, then these three values will set them firmly on the road towards success. Diligence and effort towards your goals; avoiding arrogance, acknowledging the contributions others make and remaining open to learning; and showing compassion and empathy, and treating others with respect and generosity, no matter who they are or their background or status.

At BSAK, we celebrate students who support their peers, who stay calm under pressure, who stay late around the Learning Curve or in the library to practise or rewrite a paragraph because it wasn’t quite good enough. That quiet excellence is often missed by the negative aspects of ego – but it’s where greatness grows. We are constantly striving to install this culture into BSAK students, so that they will always continue to exceed their own expectations.

Best wishes

Mr Davis

April 2025

Do It Now!

The opening two terms of this year in the BSAK Secondary School are, in many ways, the same as ever. What we are constantly doing is looking at the job we are doing as a school, and trying each year to be marginally better than we were last year. This means we are in a constant flux of review and challenge… standing still is not an option here.

I would like to use this blog as a way of demonstrating that to our parents.

Last academic year saw the opening up of our Science and Innovation block. This was so important in many ways - it allowed us to increase the number of science labs, improve the quality of science provision significantly with educationally cutting edge provision. It also allowed innovation back in the main school buildings: with an increase in the purpose built provision for the growing Sixth Form; innovation in terms of a green room for media and a groundbreaking eSports room; and provision of a personal classroom for every single teacher (no shared spaces) - this is unachievable gold dust to most schools.

However, what we started to notice last year, and have followed up on this year, is that the increased space of our school has created one negative. The number of steps taken between lessons has, on average, increased. The larger footprint means that when students travel across the campus, in particular when the students come from various places from the lesson before, it means that lesson starts are often more fragmented than they were in the past with the smaller footprint.

We investigated a hunch over the first term that this could be an issue, and it became a focus of our ‘Learning Walks’ - where senior staff go into classes to take the temperature of the learning that is taking place - an ongoing process in every great school. What we discovered was that some staff had taken to using this time really effectively, and had students thinking hard about something either to do with today’s lesson to prepare them, or to think about previous work that connected with this lesson. It is a technique that Doug Lemov calls ‘Do Now’ exercises. Doug Lemov is an American educationalist, famous for his ‘Teach Like a Champion’ book and website, which chronicles 63 techniques that truly effective teachers use.

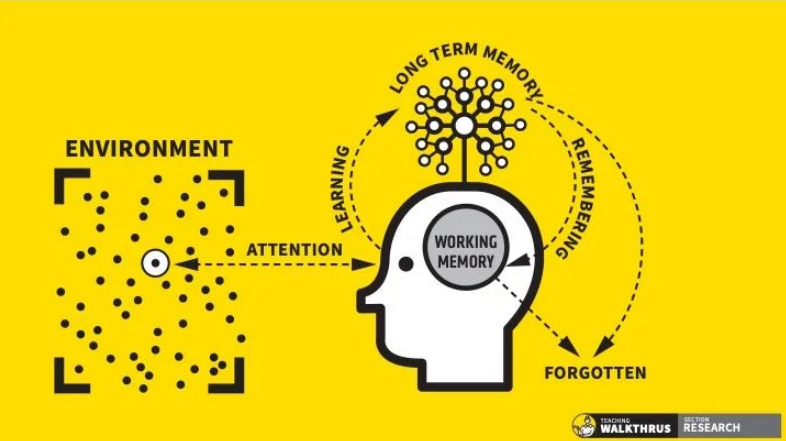

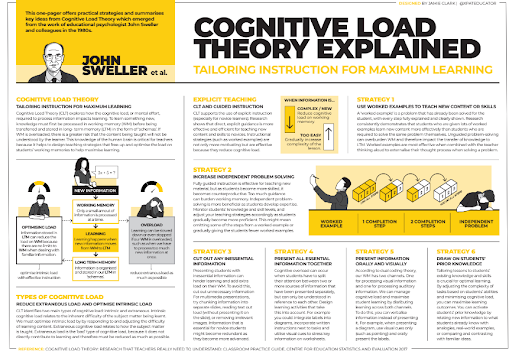

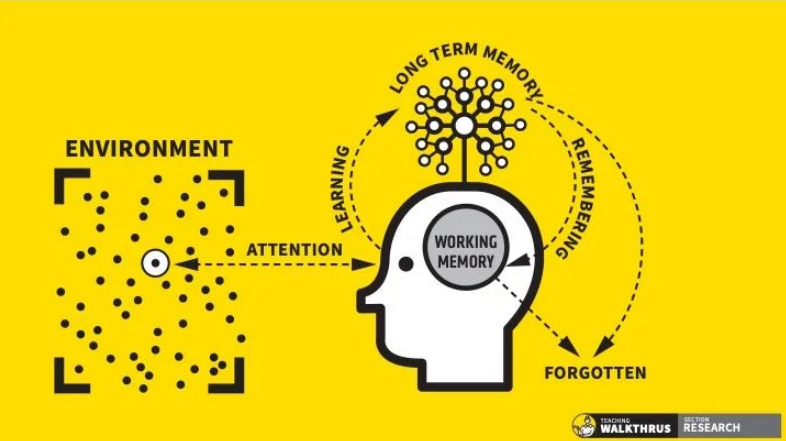

After experimenting more with the use of these, we have now rolled out the use of ‘Do Now’ starting points for lessons for all staff - the expectation being that every lesson starts with either an activity that will help gear up their minds about today’s topic, or pulls back memories from previous lessons that have links with today’s topics. Retrieving information and applying it to a new topic is a fantastic way of making those memories (or prior learnings) more ‘sticky’, as I have written about in a previous blog.

Therefore, we have aided learning in two ways by implementing this - helping with retrieval techniques to improve long term memories or prior learning, and have filled what could have been deadtime moments at the start of lessons as students moving from further locations arrive at class.

I hope you enjoyed reading this as a short inside look at how we are constantly looking to make adjustments and changes to our practice in order to continually improve our provision for our BSAK students.

With best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

March 2025

Equality, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging: EDIB

The BSAK Senior Team has been on a journey this academic year. Each month, we are being led through an EDIB course by the amazing Angie Browne - an author, consultant, and former Headteacher from the UK. It has been enlightening and challenging, as a course like this should be. It has asked us to reflect on our school and on ourselves and any potential unconscious biases that we, or our colleagues, may have. We have decided to do this because if we are going to challenge any issues with EDIB and ethical leadership, we must do this from the top of the school.

Why is EDIB so crucial, especially within a school environment such as ours? Because we need to create a space where every single child feels valued, respected, and empowered to be themselves. It’s about building a foundation for a future where differences are celebrated, not tolerated. That is what BSAK is all about.

For our BSAK students, EDIB is not an abstract concept. It's a daily experience - we have 56 different nationalities at BSAK, with a multitude of different ethnicities, cultures, religions and traditions. They learn alongside peers from vastly different backgrounds, sharing perspectives and challenging assumptions. They discover that diversity isn’t just about ethnicity or religion; it’s about gender, abilities, and individual personalities. This exposure fosters empathy, critical thinking, and a deeper understanding of the world.

Inclusion, for us, means ensuring that every student has access to the same opportunities, regardless of their background or circumstances. We strive to remove barriers to participation, whether they are physical, social, or academic. We celebrate the unique talents and contributions of each individual, recognising that everyone has something valuable to offer. We are so proud of our Inclusion Team especially, for the work they do with any student who - for a multitude of different reasons - requires a little support to ensure that the playing field is levelled, so that they can perform to their best.

Belonging is the heart of EDIB. It’s the feeling of being accepted and valued for who you are. It’s knowing that you have a place within the community, a network of support and friendship. We work hard to create a culture of kindness and respect, where students feel safe to express themselves and take risks. Every break time and after school event shows this at BSAK - last week’s Music celebration evening showed this - so many students for whom music is their life at school, coming together as a community to celebrate each other was wonderful, and I cannot wait for the community Iftars next week for both the Sixth Form and for the wider BSAK community.

We believe that by cultivating EDIB within our school, we are equipping our students with the skills and values they need to thrive in an increasingly interconnected world. They learn to appreciate different perspectives, to challenge prejudice, and to build bridges across cultures.

Last week, Mr. Byrne delivered assemblies to all students on ‘Zero Discrimination’. He discussed the multitude of different ways in which we live in an unfair world, where discrimination is sadly still present. He talked about delicate subjects, including the trouble in his homeland of Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 80s before peace was delivered.

As our students prepare to leave our school and embark on their own journeys, he talked about carrying with them the lessons they have learned in our school. Our desire is for BSAK students to become advocates for equality and inclusion, challenging injustice and promoting understanding wherever they go. They are the future leaders, innovators, and changemakers who will shape our world, and we believe that their experiences with EDIB will empower them to make a positive impact.

Mr Byrne ended with this message - That this is what real peace looks like—not erasing differences, but learning from them. He challenged our students to stand up, and do the following:

- Educate yourself. Learn about different cultures, beliefs, and histories.

- Speak up. If you see discrimination, don’t ignore it. Challenge it.

- Celebrate diversity. Talk to people from different backgrounds. Find out what makes them who they are.

The power of EDIB is not just about creating a harmonious school environment; it’s about building a better future for all. By embracing diversity, promoting inclusion, and fostering a sense of belonging, we are creating a generation of young BSAK Alumni who are committed to creating a more just and equitable world. We are not just educating students; we are cultivating global citizens who understand the power of difference and the strength of unity. And that, I believe, is the most powerful legacy we can leave.

With best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

February 2025

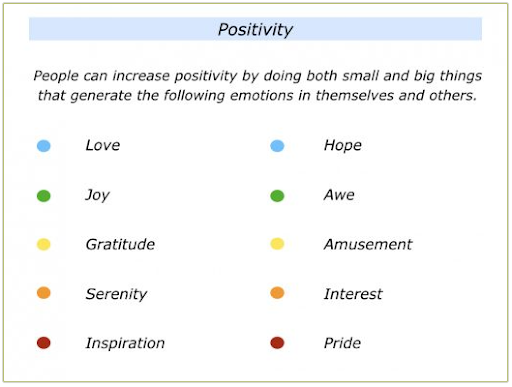

The Enduring Power of Love: A Lifeline for Teenagers

As it is February, with the western culture of ‘Valentine’s Day’ on the horizon, I thought I would take the opportunity to write about love. Not the romantic love that Valentines is about, but the sense of belonging, bonds, and support that love and community can bring. I would argue that one of the reasons why BSAK is such a very special school is because our staff truly do love our students, and (almost always), our students love each other, and almost all truly love the school.

For teenagers, their world is changing rapidly as is their place within it. This brings immense pressure and uncertainty, whilst also undergoing huge changes to their bodies and psychology; thus leading to a time of vulnerability and potential isolation. In this crucial period, the power of love – the steadfast support of friends, the unwavering love of family, and the sense of belonging within a community – becomes a vital lifeline. At this point, I think it is important to celebrate the superb students that we have at BSAK, celebrate the community that we have as a school; and celebrate the families that we have at BSAK (no family unit is perfect, but as a holistic judgement, I would say that we are truly blessed with our parent body).

It is often frustrating for parents of teenagers (I know it was for me), that friendships are often the epicentre of a teenager's world: a place where they seek acceptance, understanding, and a sense of belonging. But these peer connections provide a crucial testing ground for social skills, a place to explore identity, and a refuge from the pressures of home and school. The laughter shared with a close friend, the late-night talks about hopes and fears, the shared experiences that create lasting memories – these are all testaments to the power of platonic love in shaping a teenager's sense of self and their place in the world. It is often in these friendships that teenagers learn about empathy, compromise, and the give-and-take of healthy relationships.

However, the love from a teenager’s family, even amidst the inevitable push-and-pull of adolescence (that we all have to endure at times!), remains an absolute cornerstone of a teenager's well-being. While teenagers may sometimes seem to be pulling away and asserting their independence, the underlying need for parental love and support remains constant. Knowing that there is a safe haven, a place where they are unconditionally loved and accepted, provides a crucial sense of security during this often-tumultuous time. Of course, you know that one of your key roles is to offer guidance, even when it's met with eye-rolls, and provide a sense of continuity amidst rapid personal change. It's within the family structure that teenagers learn about values, responsibility, and the importance of commitment. Even if family dynamics are complex, the fundamental need for connection and belonging remains a powerful driving force.

We know that schools are sometimes challenging places for some teenagers as they grow and move through the tribal time of the adolescent years. Academic pressure, social anxieties, and the constant comparison to peers can take a toll on their self-esteem and mental health. The support of friends and family can make all the difference in navigating these challenges. Knowing that they have people who believe in them, who will listen without judgment, and who will offer encouragement can help teenagers build resilience and persevere through difficult times. Love, in all these forms, can be the anchor that keeps them grounded when the waves of adolescence threaten to overwhelm them.

Beyond the individual connections, a sense of community that a school like BSAK can provide, ensures our teenagers have a broader sense of belonging and purpose. Whether it's through involvement in sports teams, the various enrichment clubs, volunteer organisations such as the charities committee, or performing arts events such as YMOG or the school production, connecting with others who share similar interests and values can foster a sense of identity and create opportunities for positive social interaction. These connections can provide students with a sense of purpose beyond themselves, helping them to develop empathy, compassion, teamwork, and a sense of responsibility to something larger than themselves.

Strong social connections are linked to improved mental health, reduced stress and anxiety, and a greater sense of self-worth. Love, in its broadest sense, can act as a buffer against the challenges of adolescence, providing a sense of stability, support, and belonging. It can help teenagers develop resilience, navigate difficult emotions, and build the confidence they need to explore their identities and pursue their dreams as they head into life beyond the BSAK walls.

Each young person is unique, so each of their paths may be different, and cultivating these connections may require a lot of effort at times. It might mean reaching out to a friend, breaking the social stigma of participating in a school activity for the first time, or simply spending more time with family. It also means learning to communicate effectively, to express their needs and feelings, and to listen to others with empathy and understanding. Parents and BSAK staff can play a vital role in supporting teenagers in these endeavors, creating opportunities for connection, modeling healthy relationships, and providing guidance and encouragement.

Ultimately, love, in all its forms, is essential for young people navigating their way through their Secondary School life. It provides the foundation for healthy social development, fosters resilience in the face of challenges, and empowers them to navigate the complexities of adolescence with confidence and hope. By nurturing these vital connections, we can help teenagers thrive, not just survive, during this crucial period of their lives. Let us recognise the enduring power of love for our amazing BSAK students, and continue to always provide it!

Best wishes

Mr Davis

January 2025

New Year Reflections

Happy New Year, everyone. As we step into 2025, I hope you’ve all had a restful and joyful holiday season with your loved ones. This is an unusual blog for me, as I am not pushing some new reading or learning your way.

I know that the New Year is traditionally a time for grand resolutions - promising to make ourselves eat healthier, exercise more, or take up that hobby we’ve been putting off. But this year, instead of making a resolution I am bound to break, I’m using this time to reflect and contemplate the direction of our BSAK Secondary School community. Where are we going? What’s working well? And where can we grow together to make an even better school?

At the heart of this reflection is a commitment to continue being a "teaching for learning" school. This might sound like an obvious statement—of course, we teach for learning! But in practice, this means we’re deeply focused on using the best methods from cognitive science to ensure our teaching truly supports how students learn - much of which I have shared over these monthly blogs. Education research has shown us so much about memory, understanding, and skill acquisition in recent years, and we’re constantly looking at how we can apply these insights in our BSAK classrooms. This could mean refining how we structure lessons, revisiting how we approach assessments, or even tweaking how we support students’ independent study habits. Ultimately, our goal is to help every student learn in the most effective, engaging, and meaningful way possible.

Equally important is our unwavering commitment to our BSAK school values:

Endeavour & Resilience: We want every student to push themselves to be their best and to bounce back from setbacks. Challenges are not roadblocks but opportunities to grow.

Empathy & Care: Our community thrives when we look out for one another. This goes beyond just being kind; it’s about truly understanding and supporting those around us.

Respect & Inclusivity: Every individual in our school has a voice and a place. Our differences make us stronger, and we celebrate the diversity that enriches our community.

Honesty & Integrity: These qualities are non-negotiable. They underpin everything we do, both in and out of the classroom, building young people who are ready to make a truly positive contribution to our world.

These values aren’t just words on a poster; they’re the foundation of who we are as a school. Staying true to them means constantly checking ourselves. Are we living these values daily? Are we teaching them? Are we modeling them for our students? It’s a shared effort that involves staff, students, and parents alike.

And speaking of shared efforts, I can’t emphasize enough the importance of partnership. As parents, you are integral to everything we do. When schools and families work together, the results are remarkable. Whether it’s supporting homework routines, attending events, or simply sharing insights about your child’s needs and experiences, your involvement makes a difference. Last term, I was delighted to see so many parents in the school attending events such as the Wellbeing sessions, the One Stop Shop workshops, the discussions on Artificial Intelligence and how it can be used positively to improve the lives of BSAK students (and staff!), and to engage in our Inclusion coffee mornings. This year, let’s continue to strengthen this partnership. Your feedback, ideas, and support are invaluable as we navigate the challenges and joys of secondary education together.

Looking ahead to this year, there are some key areas I’m particularly excited about:

Academic Excellence: Helping our Students achieve the very best grades possible must be our core aim, and so enabling them to move onto their next phase of education. We’re fortunate to have students who strive for greatness, like Year 13’s Maya Telang, whose achievements span everything from stellar academic results to an impressive EPQ on AI applications in the upstream oil industry. She’s also a gifted opera singer with her own YouTube channel that showcases her talent. Students like Maya remind us of the importance of fostering both academic rigor and creative expression.

Supporting the Whole Student: Success isn’t just about grades. It’s about nurturing well-rounded individuals who can think critically, empathize deeply, and contribute meaningfully to the world. Our focus on mental health, extracurricular activities, and personal growth will continue to be a priority. We continue to work with outside agencies to ensure that our provision for our students is as strong as possible.

Innovation in Learning: In particular, the innovations that Artificial Intelligence can bring us. As we integrate these new technologies and methods, we’ll remain grounded in our "teaching for learning" philosophy. The aim is not to use tech for the sake of it, but to enhance and advance the learning experience in ways that genuinely matter. AI is clearly the tool which is exciting us as educationalists the most - as long as we wield its power correctly, and ensure that our students are educated in its use so that it is helping, not harming, their progress.

Community and Connection: Building a sense of belonging is crucial. This year, we’ll look for even more ways to bring students, staff, and families together. From school events to parent workshops, there’s so much we can do to strengthen our bonds.

Opportunities: This is really the golden egg that is BSAK. We always call ourselves a ‘busy’ school - and working here is a little like being on a treadmill that is on a speed that is just a little too fast - and that is due to our staff wanting to offer the very best opportunities for our students. This term alone (in a very short 10 week term) we have 12 Secondary School trips, 3 BSME tournaments, the BSAK 7s, Young Musician of the Gulf (that we are hosting this year for the first ever time), several art and drama workshops, competitions, concerts, book sales, Epic House Week, and taster days - being a BSAK student is a rich and diverse experience!

As we embark on this New Year, I’m filled with a huge amount of optimism and excitement. We have so much to be proud of at BSAK, and so much to look forward to. But most importantly, we have each other. Together, as a community, we can ensure that our school continues to be a place where students thrive—academically, socially, and emotionally.

Thank you for your ongoing support and for being such an essential part of our journey. Here’s to a fantastic year ahead! As always, your thoughts and feedback is most welcome.

With best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

December 2024

Do we all know our inner ‘chimp’?

How often do we all (Parents, Teachers, Students) beat ourselves up over something we did that we then look back on with agony thinking ‘why’?! Maybe it was something we did (snacking on the chocolate in the fridge, typing and sending a message in anger, or wasting an hour doom scrolling when there is something you know you need to get done); or something you didn’t do (not apologising out of stubbornness, or not putting your hand up to do something because you know that it would put you out of your comfort zone and fill you with anxiety - even though you know it would be good for you)... these are typical decisions that Dr. Steve Rogers tells us are made by our ‘Inner Chimp’ - the part of the brain that reacts instantly - but can be trained to only be listened to in a positive way, so that everyone’s mantra can change from ‘Easy choices, hard life’, to ‘Hard choices, easy life’!

Last month, I was fortunate to attend a conference in London given by the British Schools Overseas’ Association. There were many great speakers, including Adam Peaty - the triple gold medal winning olympic swimmer, who talked about his work with Dr. Steve Peters and his ‘Chimp Management’ group and how it had helped him optimise his performance and gain that 1% extra that all elite athletes are looking for, by truly understanding his mind. Also presenting was Leonie Lightfoot, from ‘Chimp Management’, who has personally supported olympians and top sports people such as Steven Gerrard.

Chimp Management comes from the book ‘The Chimp Paradox’, a concept from Dr. Steve Peters. It is a psychological framework that explains how our minds work and how we can manage our emotions and behaviors. It simplifies the brain into three main parts:

1. The Chimp (emotional brain): Represents the impulsive, emotional, and survival-focused part of the brain. It reacts instinctively and often irrationally, driven by fear, anger, or excitement.

2. The Human (rational brain): Represents the logical and rational part of the brain. It focuses on facts, reason, and long-term goals.

3. The Computer (habitual brain): Stores memories, habits, and automatic responses, acting as a reference for both the Chimp and the Human.

The idea is that the Chimp often acts first, leading to emotional or unhelpful reactions, while the Human can step in to take control with rational thinking. By understanding and managing your "Chimp," you can improve decision-making, relationships, and mental well-being.

Some of the examples given were when the chimp inside all of us gets involved and either interferes, sabotages, or hijacks our thoughts and responses to become those which we would rather they didn't! The chimp leads us to doubt and to regret decisions made in haste, or even being ‘caught in headlights’ and therefore not doing things we know we really should… Does any of that sound familiar? It certainly did to me - we all have a hidden ‘chimp’, who takes over at times…So how do we make sure it doesn’t become overbearing in our daily life - as a Student or an adult?

The framework emphasizes self-awareness, emotional regulation, and practice in aligning the Chimp and Human parts of the brain for better outcomes. Our inner chimp can be very helpful at times - it can help overcome our rational and logical areas which can sometimes stop us making that big leap of faith, or can stifle ambition…But we have to take care. Rehearsal, Practice, and Reflection before events can be so helpful. Students especially can be guilty of drifting through their life and letting it happen around them, rather than thinking hard about it beforehand, and reflecting on how they can do it better next time.

It can also really help improve our wellbeing, by working out what our chimp impacts us with - perhaps procrastination, perhaps avoidance of exercise - and then working out how we stop that chimp from impacting us in this way…Being reflective about how we approach our lives is extremely powerful, and is something we should all attempt to do more often. I know I have been over the last few weeks!

With best wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

November 2024

Metacognition - the Ultimate Dream!

This month I am writing about a state that we are all hoping to achieve within our students. It is known as metacognition. If you haven’t heard of it, I would not be surprised, because although the word has been around since the 1970s, it has only been the last 15 or so years where it has permeated through to schools.

Having our students use metacognitive approaches to their learning is often called achieving ‘self regulating learners’... so what does this mean, how can it help their learning, and what (if anything) can parents do to help this process?

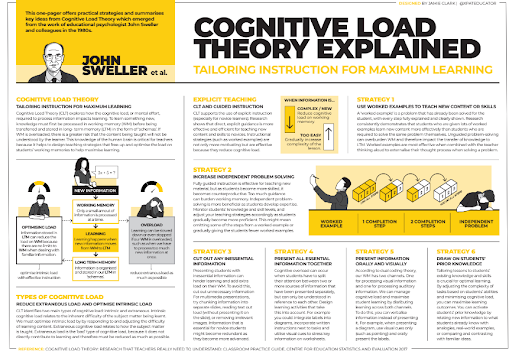

We know (and you will know this if you have read previous blogs) that ‘learning’ is really a change in our long term memory; and ‘memory is the residue of thought’ (that is a direct quote from Daniel Willingham). So what do we mean by this? When we think about something, inside our brains, our 100 billion neurons are stimulated and move about. When we make a connection and learn something, what has happened is that specific neurons have linked together to create a neuron chain; when we have these links, it means that when someone asks you a question, you are able to retrieve that information - your memory has worked!

However, neurons are slippery, which is why we often ‘forget’ over time. We also know that the best way to make those links stronger is by thinking more about the thing you are trying to remember.

This is where metacognitive strategies come in. Metacognition is essentially ‘thinking about your own thinking’, which is why it is often known as ‘self regulation’ in learners. There are several ways that students can self regulate:

- Thinking about their own thought processes. What we mean by this is - particularly when dealing with procedural knowledge (the knowledge of how to do something) is purposefully talking through the process of how to do something until it becomes embedded and second nature…For example, when you drive your car, you do it tacitly - the processes are now fully embedded. However, when learning how to drive, you have to think really carefully - did anyone else's driving instructor make you say out loud “Mirror, signal, manoeuvre”? This is a classic example - and ask teachers, we try to drum into students the really crucial bits of procedural knowledge and purposefully think about them - thinking hard about their ‘inner voices’ for processes.

- Actively monitoring and modifying their own work. What we mean by this are things such as the students thinking about what they need to do to do their work to the best of their ability; thinking about what previous work or learning will help with this piece of work; have I really understood what I need to do to succeed in this piece of work; and how am I doing with this work - is it the best I can do, or do I need to try a different strategy?

- Reflection and revision of work. When students finish a piece of work, without metacognitive strategies, they put their pen/pencil down and relax… but with metacognitive strategies, there is a lot of work they can do to either improve it, or improve themselves and their next bits of work. So, have students self evaluated; have they checked the work through and asked themselves why they have done it like this and is it definitely the right way; when they complete an assessment, have they reflected on their revision techniques honestly and consider if they need to change anything in their next preparation?

If we are being honest, when thinking back to our own school days, how many of us would confess to not really being ‘present’ in the classroom - how many of us would admit to not really thinking hard about the learning…Metacognitive strategies are about truly focussing on what makes learning happen - and this is why it is the elusive dream of all educators: if we can create the ethos of all students thinking really carefully about their own thinking, then learning will be significantly improved.

As parents, your contribution to this can be really powerful. Encouragement - especially through the start of secondary school can bring about really crucial habit forming. The ages between 12-15 is where metacognitive development seems to be at its height, so this is where it is truly key. Encouraging independent self regulation at home, and asking your children to explain things to you can encourage them with these habits…habits that will stay with them, and really help them, throughout their learning journey.

As ever, any thoughts, questions or feedback is very welcome.

With best wishes

Nigel Davis

Head of Secondary

October 2024

WOW- HOW DO THEY DO THAT?

This month’s blog is a little unusual. I try to set this blog around an article or book. But this month is based around two BSAK people. Two pretty amazing people - both of whom I have been fortunate to sit down for a chat with at the start of this term - and whose stories, for different reasons, really resonate with what being a BSAK superstar really means:

Firstly, Einass. Einass is a BSAK Year 12 student, which in itself doesn’t make her remarkable. She is studying A Levels in Maths, Further Maths, Physics and Chemistry. That does make her pretty remarkable to take on that challenge; but it is more than just that.

It is Einass’s GCSE results that set her apart. Einass achieved 11 (ELEVEN) GCSEs - ALL of which were at the very top mark - Grade 9 (the A** grade). Amazing.11 grade 9s!

I sat down with her in the first couple of weeks at school. Firstly to congratulate her, but also to chat about the future and her dreams, and how she achieved her absolutely incredible results. Einass is a very unassuming person. She does not shout about her successes, but has a quiet confidence in herself, which is truly refreshing. She has long term goals - to join her older brothers and study at one of the top London universities, and this helps her keep pushing. I was interested in finding out if she found her success easy to come by (that is, is she simply a natural genius), or did she work her socks off. Interestingly, it falls a little between the two.

When I asked her about how hard she had to try in her preparation for her exams, the answer was that she actually did not find it too hard; however, this belied her actual efforts, as she then added that this was due to all the hard work she had put into Year 10. Throughout Year 10, each week and / or weekend, she would set aside time (a couple of hours) to go back over her week’s classes and her notes to make sure that she truly knew and understood them. This meant that in Year 11, firstly, all the new learning was fairly easy to understand, as it built on the foundations from Year 10, and it also meant that her GCSE revision was much easier as she found that going over the Year 10 work was really easy as it had already ‘stuck’.

A salient tale for Year 10 students, and also Year 12 - each of which is the first year of a two year course - work hard in the first year, and you reap the benefits in the second!

I also sat down with Nikolai - for slightly different reasons. Nikolai is in Year 13, and I wanted to catch up with him to celebrate his achievements on his bike - Nikolai is the UAE Federation League Youth cycling champion. He has tremendous drive and aspirations to reach the very top in his sport. The weekend before I spoke to him, he did something that is not out of the ordinary for him - he was up at 3am getting ready to go out on a huge 4 hour ride. In the last year he has been riding not just in the UAE but also in Europe with the best riders in his age group from across the world.

Reflecting on his cycling, Nikolai told me that he had to be really honest with himself about the type of rider he can be. For him to reach the professional level, he knows that, at well over 6 foot tall, he will struggle to be a ‘climber’ - so he works incredibly hard on the type of rider he can become, and works hard on his race tactics and power cycling. He sets himself small goals, and maintains a discipline which has meant that each passing month he gets stronger - which then spurs him on even more - he told me that the stronger you feel, the more you enjoy the race.

He has goals that are short, medium and long term. His goal this year is to win the under 23 UAE event - we wish him all the best for this, and really hope that his desire to turn professional is met - he deserves it.

Both wonderful stories of grit, determination, planning for success, and atomic habits that add up to create wonderful results. There are many lessons from both of these wonderful BSAK students that others can learn from.

With Best Wishes

Mr Nigel Davis

September 2024

New beginnings

Welcome back to a fresh new academic year at BSAK. Every new school year is a perfect time to think about new beginnings, re-invention, and breaking free of an old set of habits and bursting out as a changed person - just like a beautiful new butterfly bursts free from the chrysalis.

My Dad, who sadly passed away this summer, was an avid lepidopterist - he absolutely loved butterflies - so much so that he chose to live his last 20 years in a particular part of Andalucia in Spain that is home to over 40% of all European butterflies species; he would spend most of his days wandering meadows and mountains and could recognise a butterfly simply by the pattern of its flight. Oddly enough though, as a really keen gardener, he was not at all keen on certain caterpillars which would devastate his garden plants!

But when the change happened, and the amazing butterfly emerged, it was a particularly magical thing for him.

The new school year is our students’ chance to break free of anything that held them back last year. And we can all play a part in that. Parents in particular can be incredibly powerful in terms of guiding their children to be reflective and to think consciously about habits that can be changed so they can be an even better version of themselves.

This month’s book push is by James Clear. I am going to admit that I haven’t read the book (yet), but it was mentioned in a great blog that I read from Isobel Stevenson called ‘The Coaching Letter’. So I did what many of us now do and used an AI tool to give me a synopsis of the book (is that cheating?!).

Here is my summing up of that synopsis:

It is a ‘self-help’ book which looks at the science behind habit formation. The central premise is that remarkable results can be produced by implementing small changes (the eponymous ‘atomic habits’). These are 1% (marginal) gains every day, rather than drastic big changes. The book argues that we should focus on the person we want to be rather than the person/characteristics we want to change. There are four simple rules to create good habits - ‘Make it Obvious’, ‘Make it Attractive’, ‘Make it Easy’. And ‘Make it Satisfying’. Finally, shape your environment to make it easier to succeed - and, of course, having supportive parents is a huge part of this for our BSAK students. Having parents who will go through the process with their children; coach them through the change in habits, help them commit to the changes, touch base to regularly see that they are being successful, and reward that success.

So here is the challenge to you - have you chatted to your child to coach them through some honest self reflection and discussed what they may want to change for this new school year? Are there small things they can change to make them even closer to the person / learner they want to be? Can you help them make these small changes attractive, easy, and satisfying? Can you help them in their drive, and reward their successes?

Seeing a beautiful butterfly fluttering around is great - but to witness and play a part in the change into that beautiful creature is absolutely magical. Good luck to all as we help our students / your children grow just a little more amazing day by day.

Mr Nigel Davis

July 2024

To Belong. To Bond. To have Community. Essential elements for success.

I am sure that many of you, like I do, have a special rush of pleasure whenever you see a pod of dolphins. We are so lucky here in Abu Dhabi to be able to spot them fairly regularly just off shore. Dolphins are incredible creatures, who spend their lives in small communities, called pods. In these pods, they play, babysit, alert each other to danger like predators, practice courtship, and hunt together; it is the pod community that helps them grow and survive - they are stronger together. There are many examples of this in the animal kingdom - wolves, meerkats, elephants are some that come to mind. Humans, of course, are no different. Having a strong community surrounding you is truly vital for a person’s success, happiness, and even health. It is therefore, something that we should all try to foster. This should be within the very close family community, and also in our school community. I am very proud of our BSAK community, and also feel that it is something that none of us should take for granted.